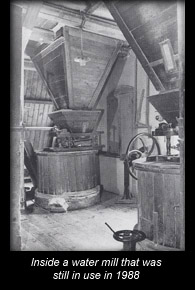

Old landscape painters with their idyllic scenes portraying lifestyles of times captured in their paintings gets many of us into that nostalgic mood. The romanticism sometimes does not quite do justice to the hard living conditions encountered in those days. The windmill on the open plain or up on the hill quietly slicing its wings through the air, or the gristmill rhythmically splashing the water over its wheel, are both in their inside mechanisms producing flour from wheat berries (kernels), compared to the modern machinery where you need to put earplugs or earmuffs on to reduce the noise; communication can only be achieved by hand signals, or yelling, etc. In the Miller and Baker you can appreciate the close relationship of these two occupations in the past history they shared. Old landscape painters with their idyllic scenes portraying lifestyles of times captured in their paintings gets many of us into that nostalgic mood. The romanticism sometimes does not quite do justice to the hard living conditions encountered in those days. The windmill on the open plain or up on the hill quietly slicing its wings through the air, or the gristmill rhythmically splashing the water over its wheel, are both in their inside mechanisms producing flour from wheat berries (kernels), compared to the modern machinery where you need to put earplugs or earmuffs on to reduce the noise; communication can only be achieved by hand signals, or yelling, etc. In the Miller and Baker you can appreciate the close relationship of these two occupations in the past history they shared.

In this article I want people that also like to go back to the way things were, or want to live more health conscious, to realize a few important facts about milling your own flour.

A kernel of wheat can retain it's sprouting (life giving potential) for thousands of years if stored properly: dry and cool. Grain found in ancient tomes of different Egyptian pharaohs have been sprouted successfully and readily give evidence to this fact.

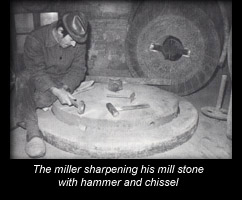

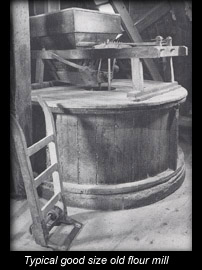

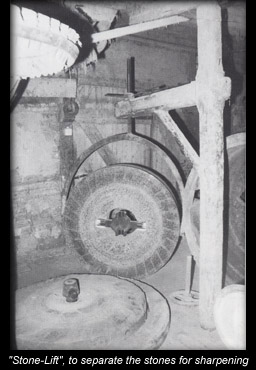

In the old days there really was only one way to grind flour and that was with different arrangements of two stones that would be turned against each other; the kernels would usually enter at the top and exit at the sides of the stones as flour. One thing the ancient bakers and millers realized quite quickly from the beginning, is that the flour would not keep for very long. Granaries were built to hold the grain until it was ground into flour. It was then used up completely within a short period of time, minimizing waste and spoilage. The reason for this is simple: the germ that contains the life-giving force (including fats), gets ground with the rest of the kernel, exposing the fats to the air, which in turn, begins the process of oxidization. This starts as soon as the grain is ground into flour, and progresses rapidly as it ages. Initially you cannot taste it, but with more time, the flour smells and tastes disagreeable, as the fats become rancid, and the flour becomes inedible. In the old days there really was only one way to grind flour and that was with different arrangements of two stones that would be turned against each other; the kernels would usually enter at the top and exit at the sides of the stones as flour. One thing the ancient bakers and millers realized quite quickly from the beginning, is that the flour would not keep for very long. Granaries were built to hold the grain until it was ground into flour. It was then used up completely within a short period of time, minimizing waste and spoilage. The reason for this is simple: the germ that contains the life-giving force (including fats), gets ground with the rest of the kernel, exposing the fats to the air, which in turn, begins the process of oxidization. This starts as soon as the grain is ground into flour, and progresses rapidly as it ages. Initially you cannot taste it, but with more time, the flour smells and tastes disagreeable, as the fats become rancid, and the flour becomes inedible.

It is helpful to slowly grind the wheat to keep the temperature of the flour down. This will extend the storability of the flour, but doesn't eliminate it from becoming eventually rancid. Modern milling techniques, through a complex rolling mechanism, break the kernel into small pieces, initially expelling/separating the wheat germ before the rest of it is ground into flour; this way the flour becomes storable for a much longer time. The primary reason for many people that want to grind their own wheat is to include the healthy contents of the germ, giving them the benefit of its important trace minerals.

The problem really is two folded. First the flour is ground on relatively small mills, which usually heats the flour up, further encouraging the problem of rapid oxidization, and the flour is then usually stored for too long. On these small mills it can be a daily chore to grind your wheat flour to avoid being exposed to unhealthy rancid flour. Store it at maximum for only two or three days before use. The possible health benefits by including the germ are annulled or even become a health hazard if not adhered to this ritual adamantly. The problem really is two folded. First the flour is ground on relatively small mills, which usually heats the flour up, further encouraging the problem of rapid oxidization, and the flour is then usually stored for too long. On these small mills it can be a daily chore to grind your wheat flour to avoid being exposed to unhealthy rancid flour. Store it at maximum for only two or three days before use. The possible health benefits by including the germ are annulled or even become a health hazard if not adhered to this ritual adamantly.

The rye grains and its subsequent flour are not as critical. This is due to its structural differences, as well as the characteristic makeup of its fats.

We have a fair size stone flour mill which I use every other day to grind wheat on, but I am reluctant to grind anyone else's wheat. First of all, it is set to my own specifics, applied to my bakery needs, and second of, the amount of grain needing to be ground always tells me that it will be stored and used for the next few months, as opposed to the next few days. The purpose of grinding your own wheat becomes an irony, and counter productive.

Another important thing for anyone considering buying or milling his or her own flour is the type of mill. There are basically only two types: stone (including ceramic) and metal. The stone mills are much better equipped for milling wheat flour; the larger the surface area and the slower speed at which the grain is milled, will determine the temperature (preferably cooler) and slow the onset of the ensuing oxidization process. Mills that are equipped with metal plates might produce a lot more flour in a given time, but this raises the temperature of the flour, and the fats of the germ are not only exposed to air, but also make contact with the metal of the plates, further encouraging spoilage.

A good stone mill can easily run in the thousands of dollars with very small mills already in the hundreds. You have to be devoted and really appreciate freshly ground flour, but be aware that baking with fresh flour harbours its own challenge.

All of our breads contain some amount of freshly ground flour, but we mostly use flour ground in big modern flourmills. There are two decisive points of why we don't grind all of our own flour. Firstly the expense of a large enough stone mill, and secondly, a person has to consider that the problem of the germ going rancid is eliminated through modern milling techniques. Because the wheat germ has to be removed undamaged by this process: it is only lightly squeezed, and not ground, which allows us to reincorporate it into the flour prior to making our dough, which is exactly what we now practice. All of our breads contain some amount of freshly ground flour, but we mostly use flour ground in big modern flourmills. There are two decisive points of why we don't grind all of our own flour. Firstly the expense of a large enough stone mill, and secondly, a person has to consider that the problem of the germ going rancid is eliminated through modern milling techniques. Because the wheat germ has to be removed undamaged by this process: it is only lightly squeezed, and not ground, which allows us to reincorporate it into the flour prior to making our dough, which is exactly what we now practice.

For any health conscious person that cannot afford or expend the time it takes to grind your own flour, it is a good alternative to buy whole-wheat flour, and the germ separately, then combining them into whole grain flour before use. This way it eliminates the gamble of eating rancid flour.

My personal dream is to build a gristmill on Kaslo river and grind our town's own flour on a daily basis. There is even an ideal location where in the old days a hydroelectric plant was built that supplied Kaslo with its first electricity: the concrete structure of it is still in place. The economic viability of a project like that would be rather slim, but it sure would be exceptional.

The aim of this article was to explain the pros and cons about milling your own flour, and to point out that sometimes even modern technology can be beneficial if applied and viewed in the right light.

|